We live in an increasingly polarized world, and trade finance is no exception. The good old days when banks were able and willing to support a wide spectrum of exporters, importers, and traders are gone. Today, most lenders are chasing the same client: a well-established business with a large balance sheet and steady cash flows. And you cannot blame them for that because it is a natural response to the cost of complying with new financial regulations and the need to maintain an acceptable risk-adjusted return on capital.

In terms of compliance, some banks say that if you do due diligence properly, you may spend up to $50’000 on a single client, especially from emerging markets. In terms of profitability, trade finance remains notoriously labor-intensive. Often it takes the same time to structure and execute a $1-million transaction and a $50-million transaction.

These factors shape any lender’s appetite to trade finance.

Consequences

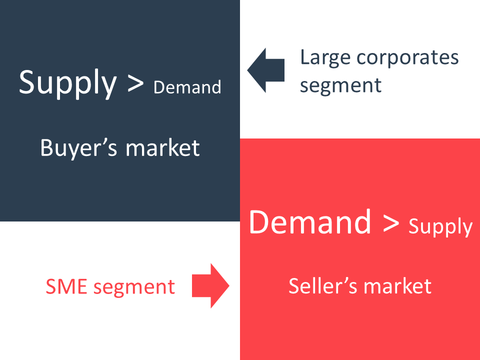

The only winners in the current situation are large multinational corporations. For the lenders, even for tier-one international banks, the intensified competition in this market segment inevitably translates into the buyer’s market and squeezed margins. On the opposite side of the client spectrum, the SME borrowers face a growing deficit of trade finance. Currently the Asian Development Bank estimates it at $1.6 trillion worldwide, which makes a quarter of all trade finance market.

So the market is stuck in dichotomy these days—the abundance of trade finance for the larger corporates and its shortage for the SMEs. It is bad for economic development because international trade is again concentrated in the hands of a limited number of well-connected players. For the banks, such concentration creates a vicious cycle, in which greater dependence on fewer borrowers puts additional pressure on margins and helps large trading houses cannibalize their lending function. For the smaller borrowers, limited access to trade finance means bleaker prospects for business development at home and abroad.

Way forward

The root cause of the current polarization lies in trade finance economics. Until recently, this business was a prerogative of the select club of banks and trading houses, which were slow to adapt to the changing landscape of global commerce. The financial crisis exposed these shortcomings and unleashed innovation in three areas: business models, financial intermediation, and technology.

Today we see the emergence of entirely new business models, such as supply chain finance, trade finance securitizations and global platforms for sharing critical data and structuring, financing, and exchanging trade-related loans and securities. These developments are driven by market participants’ realization that only a joint effort can address the needs of the industry at large, and that those unwilling to embrace change risk being left with nothing.

In terms of financial intermediation, the banks are no longer the only source of trade finance, though they still control the infrastructure to process international payments and mitigate non-payment risks. The business of non-bank lenders, for example specialized investment funds, is gaining momentum; however, their lending capacity is still a fraction of the unsatisfied demand and their funding remains costly and erratic. Fortunately, over the past decade trade finance became much better understood in the capital and debt markets and now the main question is how to link the borrowers with these markets more efficiently.

Finally, information technology can substantially reduce the cost of processing and enhance security of trade finance transactions. For example, digitization allows replacing paper documents with digital data flows; blockchain helps standardize these data flows, while smart contracts allow automating many trading operations. The adoption of these technologies will create entirely new products and services.

Implications

These developments are already changing the economics of trade finance, however, it will take some time to feel their combined effect. The progress may be slowed down by the rise of protectionism, stricter regulation of non-bank financial institutions, and petty rivalries between market participants. In the meantime, SME borrowers have no other choice but to brace for a higher cost of trade finance and to compete for it more aggressively.