The Russian economy depends on exports of natural resources and commodities. The Federal Statistics Service reports that these accounted for half a trillion dollars in 2013, or 93% of all export revenues. Oil, gas, and petroleum products fetched $377bn followed by metals ($55bn), chemicals ($31bn), and agricultural products ($16bn). European banks financed the bulk of these trade flows.

Given the structure of Russian exports, it is surprising how little Russian banks are involved in commodity trade finance (CTF), which is in stark contrast to Brazil and South Africa, the other resource-based economies in the BRICS club. In those countries, local banks not only rival established commodity financiers but also often eat their lunch.

The current standoff between Russia and Western countries tips this setup out of balance. As the economic sanctions continue and Western banks freeze or reduce exposure to Russia, some Russian exporters are looking for new sources of commodity trade finance. Are Russian banks prepared to pick up the baton?

The big picture

Origination, processing, and distribution of commodities are capital intensive. New projects, M&A, international trade, and hedging generate incessant demand for external financing. To operate in this environment, any business should extend its borrowing base.

CTF allows corporate clients to complement the traditional borrowing base—fixed assets, shares, and securities—with self-liquidating structures linked to physical trade flows. Over the past decades, these financing techniques have become an indispensable source of working capital for producers, consumers, and everyone in between.

CTF holds a large share in the global trade finance market, an industry dominated by some twenty financial groups that are mainly headquartered in OECD countries. These banks are market leaders in terms of global reach, customer service, and operational efficiency.

In a report released in 2008, Oliver Wyman forecast the global trade finance market would exceed $24bn by now, growing 5%–7% a year. The consultancy estimated that the five leading CTF banks accounted for 40% of the global revenue pool. The financial crisis increased market fragmentation because many banks—BNP Paribas is a telling example—scaled back CTF operations.

CTF market in Russia

The modern structure of financing Russian exports was shaped by several factors.

The economic reforms of the 1990s led to the collapse of the centralized system of foreign trade, while the post-Soviet banking system was unable to cope with new demand for trade finance. International traders were quick to offer Russian exporters offtake agreements backed by Western banks. It did not take long before the larger exporters started to internalize trading, shipping, and financing functions. Credit facilities with foreign banks allowed exporters to leapfrog into the international financial market, leaving domestic lenders to catch up. It was a marriage made in heaven: Western banks benefited from an insatiable demand for CTF products in one of the world’s largest markets, while Russian exporters secured efficient working capital solutions that were not available back home. The initial tie-up in CTF catalyzed cross-selling opportunities in corporate, investment, and private banking and helped create global market leaders, such as Lukoil, Rusal, and Uralkali. By the late 2000s, virtually all Russian exporters were selling commodities through dedicated trading entities scattered around the world.

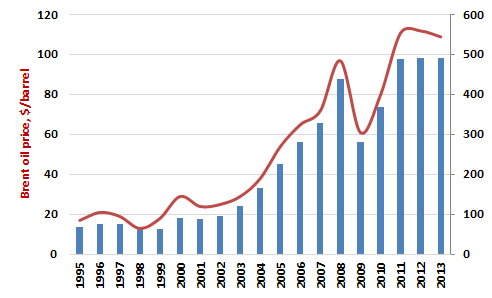

Chart 1. Evolution of Russian commodity exports in 1995-2013, $bn

This setup has survived to the present day. In the meantime, Russia abolished capital controls and liberalized its foreign exchange market; many Russian exporters became world-class businesses, and the value of commodity exports has grown six-fold, making Russia one of the largest CTF markets in the world.

Russian banks failed to respond to these developments for two reasons: On the demand side, they faced widespread offshoring of financial services by Russian exporters. Powerless to withstand this trend, they just went with the flow in the booming Russian market instead of catching up with global competition in CTF. While offshoring and hastened transition to a market economy provided foreign banks with a first mover advantage, it was the local banks’ inaction that helped them solidify control over the Russian CTF market.

Changing regulatory environment

“Today only sixteen countries in the world do not impose any foreign-currency restrictions; Russia is one of them,” declared Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, in 2007. Indeed, Russian exporters are no longer obliged to convert foreign exchange into the national currency like it happens in Ukraine, for example, where mandatory conversion reaches 75%. Local banks, however, are still required to police the execution of international contracts, and the Bank of Russia has stopped short of allowing the rouble to float freely, pegging it to the USD/EUR duo instead.

Seven years on, it seems more appropriate to peg the Russian currency to the oil price. At the time of this writing, the rouble has lost more than half its value in less than one year, while the Bank of Russia’s attempts to prop it up have cost over $100bn. Last November, the regulator stopped currency interventions, which coincided with further lowering of energy prices. Against this background, one cannot exclude the reintroduction of foreign exchange and capital controls, which is already being mentioned by some officials.

To boost tax revenue at the time of falling energy prices, the Russian government has recently passed new anti-offshore legislation. The new law on the “de-offshorization” of the Russian economy does not prohibit the use of foreign jurisdictions but redefines the notions of tax residence, controlled foreign entities, and beneficial ownership for Russian tax purposes. According to Ernst and Young, the new legislation may increase the tax burden on foreign holding and trading structures and make them less economically viable for Russian businesses.

From the lender’s perspective, a new law on security interest over movable property is another noteworthy development. It came into effect in July 2014 to supersede a patchy legal framework dating back to 1992. The new legislation streamlines creation, transfer, disposal, and termination of collateral pledged to third parties. To better protect the rights of creditors, it introduced a uniform state system of pledge registration.

These developments may have far-reaching implications for the Russian CTF market. A combination of a freely floating rouble and the “de-offshorization” of the Russian economy may place local banks in a better position to woo CTF customers from foreign banks. The new legislation should simplify the lending to exporters against the pledge of goods and accounts receivable. On the other hand, any restoration of foreign exchange controls would incentivize the hoarding of foreign currency offshore, even at the expense of a higher tax burden.

Offshoring

In the last Index of Economic Freedom, Russia was ranked 135th for respecting property rights and 149th for freedom from corruption. The survey included 184 countries.

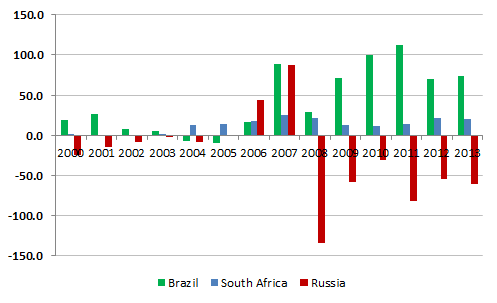

Weak rule of law perpetuates economic uncertainty and causes capital flight. From 2000 to 2013, capital outflow from the Russian economy reached a whopping $346bn. During the same period, Brazil and South Africa enjoyed net capital inflows of $606bn and $173bn.

Chart 2. International capital flows, $bn

A big part of capital leaving Russia is reinvested through holding companies in jurisdictions with a strong rule of law. In 2013 alone, Russia received $71bn of foreign direct investment, 83% of which was from the UK, Luxembourg, Ireland, the British Virgin Islands, and Cyprus—popular jurisdictions among Russian businessmen.

How is offshoring related to CTF? For any Russian exporter, the need to raise finance goes hand in hand with the need to mitigate business and political risks. International trade offers a lawful way to diversify profit centers and relocate investment activities and wealth management abroad. Foreign banks were better positioned to support Russian exporters in these activities for obvious reasons.

The last financial crisis, and especially its repercussions in Cyprus, dented the confidence of Russian business circles in Western banking practices. The current political crisis provides another argument for Russian businesses to lower their exposure to US and European banks. This change of attitude heralds juicy opportunities for Asian financial centers, from Dubai to Hong Kong.

It remains unclear whether or not Moscow will answer Russian exporters’ call. Until now, local banks have been busy picking low-hanging fruit.

Asset allocation

Since the turn of this century, the Russian economy has offered local banks generous lending opportunities, especially compared with mature markets of the leading CTF banks. According to the World Bank, Russia’s GDP growth averaged 6.2% from 2000 to 2012 except 2009, when the economy shrank by 7.8%. A strong local demand in such segments as construction, services, manufacturing, retail, and consumer credit ensured profitable growth without the need to take on the foreign banks’ grip on CTF. This approach may have lacked strategic vision but had simple commercial logic: make hay while the sun shines.

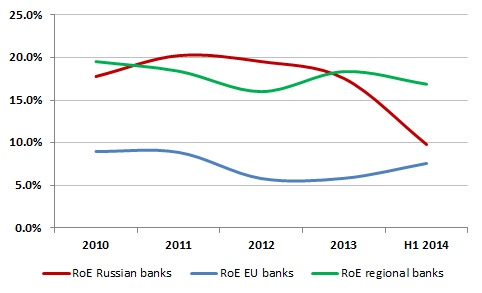

Banks rarely report on profitability of separate lines of business, which makes it difficult to benchmark CTF to other banking products. Anecdotal evidence suggests that CTF generates a 10%–15% return on equity (RoE) for leading European banks. Even so, comparing total profitability provides interesting insights into risk-return trade-offs sought by banks in developed and emerging markets.

Our express analysis (Tables 1 and 2) shows how leading Russian banks have outperformed selected European peers with a large share of CTF operations since 2010.

Table 1. Return on equity, selected Russian banks

| Bank name | Description | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | H1 2014 |

| Sberbank | Largest national bank | 20.6% | 28.0% | 24.2% | 20.8% | 17.7% |

| VTB Bank | Second largest national bank | 10.3% | 15.0% | 13.7% | 11.8% | 1.1% |

| Alfa Bank | Largest private bank | 19.1% | 19.7% | 21.9% | 20.1% | 9.6% |

| Otkritie Bank | Second largest private bank | 21.1% | 18.2% | 18.3% | 17.5% | 10.8% |

| Average RoE | 17.8% | 20.2% | 19.5% | 17.6% | 9.8% | |

..

Table 2. Return on equity, selected European banks

| Bank name | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | H1 2014 |

| BNP Paribas | 12.3% | 8.8% | 8.9% | 7.7% | 8.2% |

| HSBC | 9.5% | 10.9% | 8.4% | 9.2% | 11.3% |

| Deusche Bank | 5.5% | 8.2% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 4.6% |

| Rabobank | 8.6% | 7.6% | 5.4% | 5.2% | 6.2% |

| Average RoE | 9.0% | 8.9% | 5.8% | 5.8% | 7.6% |

..

In a recent report, Bain and Co. make a case for the rate of return on risk-weighted assets (RoRWA) to be used as a more reliable metric of a bank’s profitability. Having analyzed the financials of the thirteen largest Russian banks, including the four banks in our sample, the consultancy concluded that their average RoRWA was a meager 2.7% in 2012.

Even if Russian banks’ RoRWA was higher than the RoRWA in all European countries except Turkey and Poland, it was surprisingly lower than the average RoE in our sample (19.5%). Such wide divergence suggests that Russian banks hold too many high-risk, high-return loans that may turn sour as the economy slows down.

As if in affirmation, Russia’s economic performance has started taking its toll on its banks’ profits. A paltry (1.3%) growth in 2013 caused the half-year RoE of the sampled Russian banks to plunge below 10% and nearly converge with the RoE of their peers in Europe.

Chart 3. Profitability of selected banks in 2010 – 2014

.

A sustained rise of nonperforming loans will signal that the time of high-risk, high-return banking in Russia is over. If the lower profitability environment becomes a new normal, local banks will have to look for new areas of growth. CTF is probably the fittest candidate to top the list.

Outside the context of Russian banking, the lower profitability environment is not a precondition for commodity finance. Our further comparison (Tables 2 and 3) suggests that in other emerging markets a thriving CTF business concurs with profitability levels long unheard of in mature markets.

Table 3. Return on equity, selected regional banks

| Bank name | Description | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | H1 2014 |

| Banco do Brasil | Largest bank in Latin America | 27.0% | 22.4% | 19.8% | 22.9% | 15.5% |

| Itaú Unibanco | Largest private bank in Latin America | 23.5% | 20.5% | 16.6% | 20.9% | 23.2% |

| Standard Bank | Largest bank in South Africa | 12.5% | 14.3% | 14.0% | 14.1% | 12.7% |

| Absa/Barclays | Second largest bank in South Africa | 15.1% | 16.4% | 13.6% | 15.5% | 16.1% |

| Average ROE | 19.5% | 18.4% | 16.0% | 18.4% | 16.9% | |

..

The three factors discussed above—regulations, offshoring, and asset allocation—explain the low participation of Russian banks in CTF. The success of local commodity financiers in Brazil and South Africa, however, shows that local market knowledge and networks may trump the incumbents’ scale and expertise. The denominator of success is a bank’s ability to understand and respond to daily challenges faced by the exporter.

Building a winning value proposition

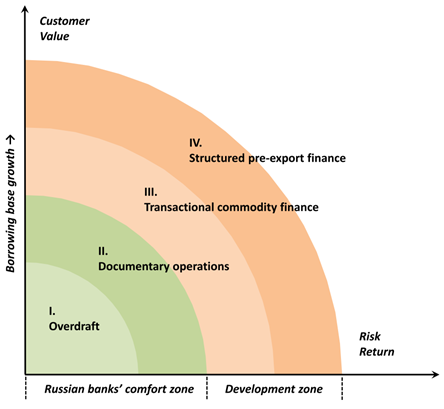

One way to understand a competitive position of any bank in CTF is to look at the interrelation between customer value, risk, and profitability. In Model 1,

- Customer value derives through efficiency of commodity finance techniques (Quartiles II, III, and IV) compared with traditional corporate finance (Quartile I)

- Return on risk-weighted assets determines the lender’s long-term profitability in each financing technique (Quartiles I through IV).

Model 1. Commodity finance: balancing customer value and profitability

..

How are Russian banks positioned in this model?

Customer value axis: understanding client needs

Exporters’ needs are focused on the following:

- Borrowing base growth: leveraging self-liquidated trade transactions to finance production and international distribution of commodities.

- Business development: extending the range of financing options to open up new business opportunities, enhance customer services, and grow sales and profit margins.

- Cost and risk management: applying CTF techniques to mitigate risks and lower the cost of working capital finance.

Our model shows how customer value increases from traditional corporate finance, where loans are secured by a borrower’s assets, to CTF techniques.

Many Russian banks market trade finance as part of their corporate finance programs. Their service offerings, however, are often limited to documentary operations. Even though such instruments make a (lucrative) backbone of any trade finance service package, they hinder exporters’ trading activities in several ways:

- Dependence on documentary credits cuts off important market segments. While a letter of credit remains the most popular, and sometimes indispensable, payment option in many countries, commodities are supplied on credit terms in the developed markets. Large corporate customers in emerging markets are following suit, which makes us believe it will not be long before trade credit is required by qualified debtors worldwide.

- Documentary operations do now allow exporters to finance inventories of unsold goods. Even if inventory financing has initially emerged as a technique to finance the middle of the commodity supply chain—processors, wholesalers, and retailers—for many exporters, it has become an important instrument of alleviating temporary imbalances between supply and demand.

- Finally, documentary credits badly fit pre-export finance, in which loans are gradually repaid from export cash flows generated over a period up to several years. For many Russian companies, pre-export finance has become a preferred technique to tap into the international financial market.

A limited range of trade finance services provided by the Russian banks may fit the bill only for Russian importers. In contrast, foreign banks have taught Russian exporters to expect financing solutions in all quartiles of our model as a matter of course. A bank that is unable to match these expectations has little chance to win an exporter’s business—or even part of it. The winner takes all.

A local bank taking CTF seriously should finance the exporter’s working capital against the following collateral:

- Presold and unsold inventories, back home and abroad

- Export accounts receivable

- Export contracts and future cash flows

Besides, the bank should finance the exporter’s logistics solutions—marine and multimodal transportation, warehousing, and distribution. The bank should also be a risk manager of last resort, helping the customer mitigate international trade risks. To provide these services, Russian banks should develop cross-functional teams embracing specialists in international trading, risk management, shipping, and commercial law.

Risk/profitability axis: striking the right balance

While secondary to the breadth of service offerings, the cost of commodity finance remains an important consideration for exporters. They are willing to pay a premium for financial services that address their needs and business objectives; however, such services may entail additional risks to the lenders.

Our model shows how risk and return increase from traditional corporate finance to structured trade finance, which requires careful assessment and management of counterparty and operational risks.

The Bain report suggests four dimensions for pricing financial services in each quartile of our model:

- Balance sheet management: the pricing of banking products based on risk and cost and the allocation of capital to business areas with higher returns

- Cross-selling: ability to sell banking products in complementary business areas

- Cost structure: a measure of operational efficiency

- Cost of risk: a measure of non-recoverable losses against risks taken

In terms of cost structure, there is a common misconception that Russian banks are less competitive because of higher cost of funding in foreign currencies, but most costs of Russian exporters are incurred in roubles, so RUB financing works just as well.

Seen from a different angle, the exporter wants to lower the real interest rate payable under the loan agreement:

Real interest rate = Nominal interest rate – Inflation rate – Cost of hedging FX risk

Exporters will naturally prefer financing in the currency offering a lower real interest rate. No wonder then that rouble financing has recently become popular among Russian exporters.

In CTF, cost of risk is a function of know-how and risk management. The rise of Brazilian banks in the local CTF market suggests these derive from strategy and investment rather than corporate DNA. The current economic environment makes it easier to acquire related skills and competencies, as a larger pool of talent is readily available. A later entry into the Russian CTF market may help local banks learn from others’ mistakes. In terms of fixed costs, a depreciating rouble provides local banks with further advantage.

***

The current geopolitical context, as unfortunate as it is, may catalyze the overdue development of commodity finance in Russia. On the demand side, the cooling of the Russian economy requires local banks to look for new sources of revenue. On the supply side, traditional lenders are less keen on financing Russian exports. As a result, some private Russian banks have recently reported overtures from large exporters, which has never happened before.

To succeed, Russian banks should analyze and build on their strengths: existing customer relationships, local market knowledge, and tolerance of political risk. As Western banks become more regulated by supranational legislation, the Bank of Russia may chart its own course to increase competiveness of local banks.

Ironically, the reliance of the Russian financial industry on large state-owned banks may abridge the development of local commodity finance—as it happened on the other side of the globe.