Last month I attended the 5th edition of the Africa CEO Forum, a two-day event dedicated to the continent’s socio-economic development. One of the forum’s key—and, unfortunately, protracted—discussions was how to end Africa’s resource curse and climb up the value chain.

As someone engaged in a natural resources business, I got the impression we’re just going around in circles, looking for answers to this question in the wrong places. Here’s our take on this topic, based on hands-on experience of working with commodity exporters from emerging markets worldwide.

Moving up in the value chain: manufacturing is not the only answer

The debate at the Forum about moving up the value chain focused on manufacturing. It is easy to understand why. According to the Economist, the share of African countries in the developing world’s manufacturing output has dropped from 9% in 1990 to 4% in 2014. Yet, very little was said about services, which offer another—more readily available—way to add value. Often it is more lucrative: Forbes reports that last year US manufacturing and processing industries came only 10th and 11th in terms of profitability.

In the context of natural resources, services represent an integral part of international business:

- From a commercial standpoint, producing something without being able to bring it to market makes little sense. Yet, a whopping number of export-oriented businesses operate that way, hitting an invisible wall every time they try to enter the international market on their own.

- Contrary to producers of technologically advanced products, which actively manage their supply chains, most consumers of commodities leave it up to their suppliers. It is suppliers who must take charge of cross-border deliveries, financing and risk management.

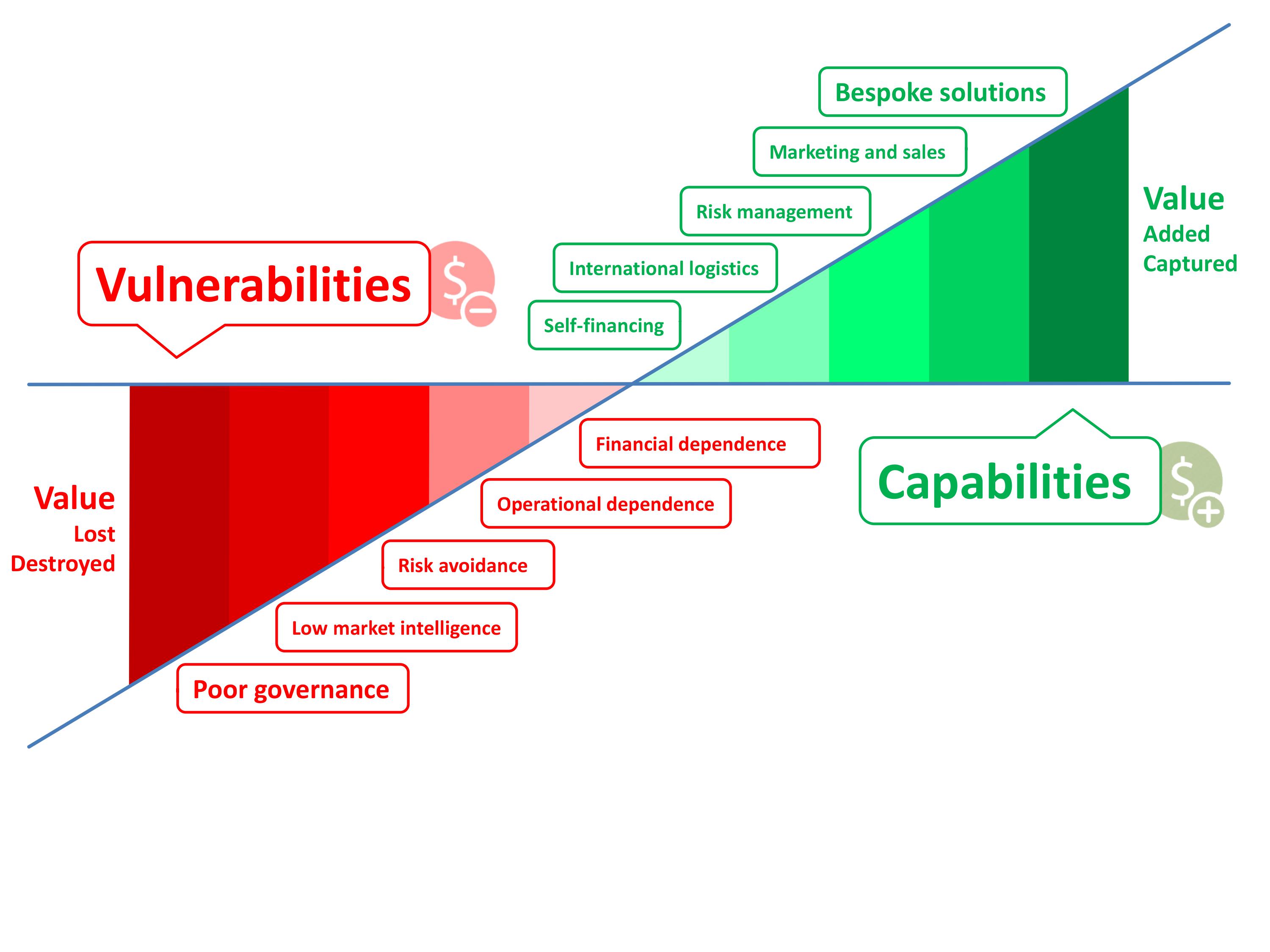

In other words, consumers of commodities need solutions comprised by physical products AND these services. They have long been primed to procure commodities this way, leaving logistics, financial and risk management services up for grabs—historically to traders and distributors, but increasingly to savvy exporters. The latter may identify and capture value through streamlined supply chains and customer services (see Figure 1).

Value-added exporting of this sort has long been a prerogative—and default approach to international business—of large commodity producers. Today it becomes available to midsize companies and export development organizations representing small-scale farmers and miners.

Figure 1. Capturing supply chain value: a zero-sum game

From Canada to Australia, commodity exports contribute to rich and diversified economies. Trade tariffs aside, their exporters enjoy unrestricted access to global commodity and financial markets. African exporters should be no different.

Moving forward in the supply chain: control or be controlled

There has been a subtle change in denoting the role of a trader recently. As commodity markets become more transparent and arbitrage opportunities fade away, a new impetus is given to managing the supply chain.

What does it mean in practice? Let me offer one example. In the past decades only a limited number of well-connected players could export grains from Russia because of structural shortages of grain handling facilities. Such infrastructure bottlenecks abound in Africa and other emerging markets. They make the whole idea of climbing up the value chain pointless because most value is appropriated by those who control critical nodes in the supply chain. Financial bottlenecks—for example, the shortage of trade finance, which exacerbated after the financial crisis—have the same effect.

Against this backdrop, taking control of supply chain management isn’t only about profits but also strategic options. At the time when global trading houses keep investing into logistics and processing infrastructure and moving upstream, national exporters’ fortunes depend on their ability to move downstream.

In a natural resources business, either you control the supply chain or it controls you. Brutal but true.

A balanced approach to economic development

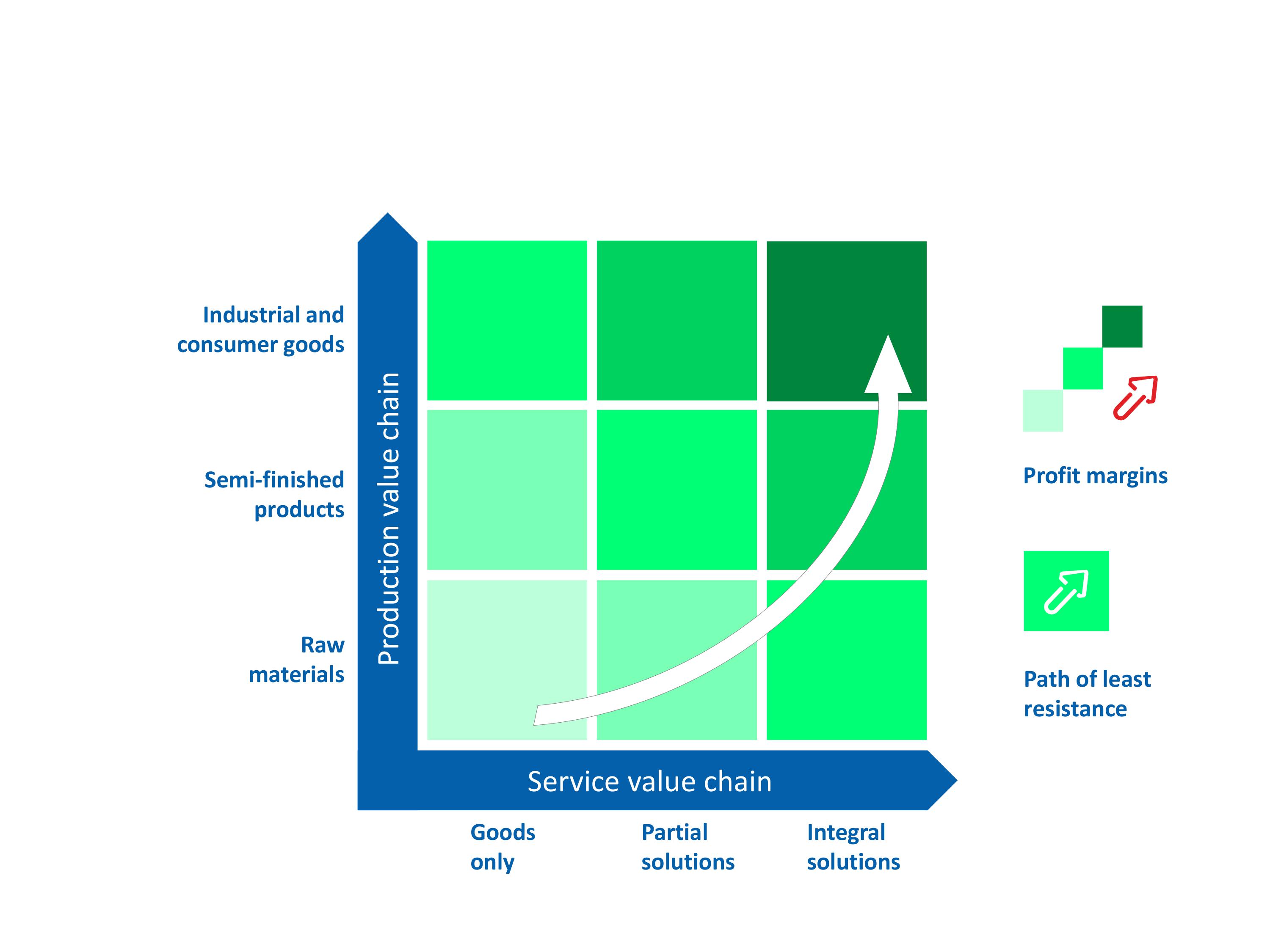

The primary reasons behind the resource curse experienced by many African countries are poor governance and economic mismanagement, not commodity exports per se. Value-added exporting offers a path of least resistance to economic development: leveraging natural resource endowments to feed a virtuous cycle of growth, investment and diversification (see Figure 2). In this respect, the development of African manufacturing is essential to “domesticate” imports produced from the very materials that Africa exports. When it comes to competing in the global marketplace, perhaps the best approach is to find the right mix between raw materials exports (such as raw cotton or green coffee), semi-finished exports (such as cotton fabric or roasted coffee), and finished goods exports (such as cotton garments or packaged/branded coffee) based on comparative advantages of each country.

In our experience, attempts to climb up the value chain before taking control over the supply chain could be counterproductive. We’ve recently worked with an agricultural exporter that heavily invested in manufacturing without paying enough attention to international marketing and distribution. Today their processing and packaging facility is world-class, however, they are unable to sell value-added products at anticipated mark-up. The domestic market is tiny while the international market is controlled by a handful of dealers. For exporters like these, it makes more sense to integrate international sales, marketing and customer services before investing into manufacturing capabilities.

Figure 2. Value? Profit? Or both?

The main hindrance to integrating these functions is market fragmentation. The more convoluted the supply chain, the more difficult it is to shift to value-added exporting. In the context of African agriculture and small-scale mining, perhaps the best approach to tackle these issues is pooling smaller producers into export development organizations. Having reached critical mass, such organizations may initiate and manage forward integration projects while sharing related costs and profits among members.

The role of policymakers

However enterprising, export-oriented businesses can only do so much without an enabling environment. This involves comprehensive policy measures and the support of multilateral aid programs, especially when it comes to the least developed countries.

The path of least resistance advocated above should not be mistaken for least effort, it is about directing the stakeholders’ resources to incremental improvements rather than grand schemes. In our view, these are more likely to accelerate inclusive growth, in Africa and beyond.

© Ruslan Kharlamov 2017